Bird Art in the Age of Discovery and Beyond: Works from the Stubblefield Collection

Simmons Visual Arts Center, Sellars Gallery

Thursday, November 4, 2021-Thursday, March 2, 2022 Reception and Gallery Talk: Thursday, February 24, 5:30-7 p.m. Free and open to the public. Information: 770-534-6263

The works in this exhibition come from the impressive collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield. The selected pieces showcase art from the 1700s to modern times and demonstrate how much art and artists’ views have evolved surrounding the scientific depiction of birds.

17th Century

Pieter Holsteyn the Younger

Pieter Holsteyn, The Younger (Dutch, 1614-1673/87), “Untitled”, Black-tailed Godwit (Limosa limosa), likely adult female in breeding plumage, Pen, ink and watercolor on paper, n.d, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Pieter Holsteyn the Younger (1614-1687) was a Dutch glass painter and engraver from Haarlem, a city outside of Amsterdam in the northwest Netherlands. Haarlem was once a major North Sea trading port. Many early species of birds from all over the known world, many new to science, made their way to her ports. Holsteyn likely painted specimens for the enjoyment of private collectors and not as studies for scientific prints. As such, there is little annotation or scientific information on the birds he depicted.

This painting is of a Black-tailed Godwit, a species that breeds from Iceland through Europe to the Russian far east and winters in Africa, Asia, and Australia. It is one of the earliest such paintings from the early modern period of history – an era marked by the beginnings of economic and scientific globalization.

18th Century

Johann Leonhard Frisch

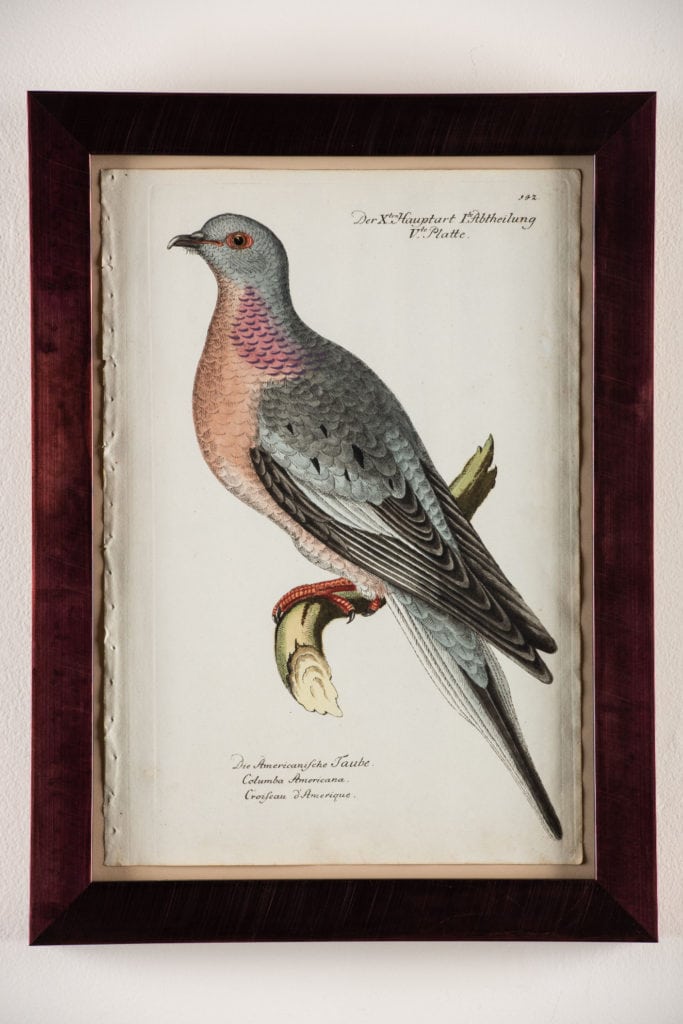

- Johann Leonhard Frisch (German, 1666-1743), Die Americanifche Taube (The American Pigeon), Plate 142″, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), Hand-colored engraving on paper, 1733-63, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

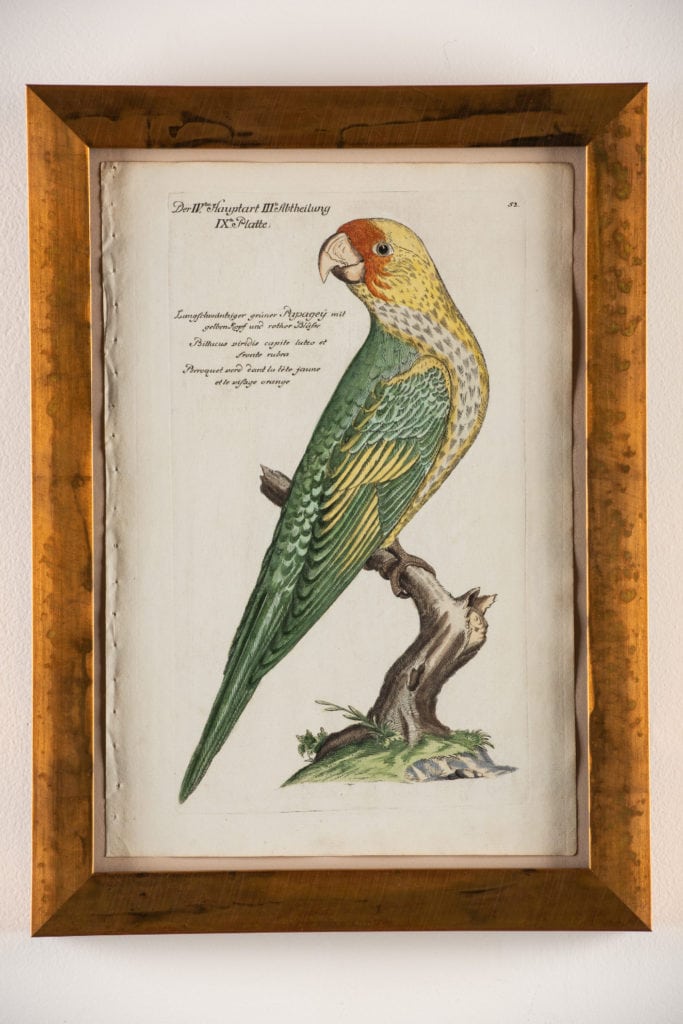

- Johann Leonhard Frisch (German, 1666-1743), “Parrot, Plate 52”, Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), Hand-colored engraving on paper, 1733-63, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

These plates depict the Passenger Pigeon and Carolina Parakeet, North American species that went extinct in 1914 and 1918 respectively. They are from Vorstellung der Vogel in Teutschland und Beylaugffig auch Einiger Fremden, mit Ihren Eigenschaften Beschrieben…und Nach Iheren Naturlichen Farbe (Presentation of the birds in Germany and Beylaugffig also some strangers, with their characteristics described … and according to their natural color). Johann Leonhard Frisch (1666-1743) began publishing the work in 1733. It ultimately included 256 hand colored plates. It was completed after his death in 1763 by his sons, Leopold Frisch, who wrote the text, and Ferdinand Helfreich, who together with Philip Jakob Frisch, engraved and colored the plates. The last 30 plates were by Johann’s grandson Johann Christoph Frisch. The work is divided into twelve parts for the different bird families and covers European and some exotic species.

Christoph Ludwig Agricola

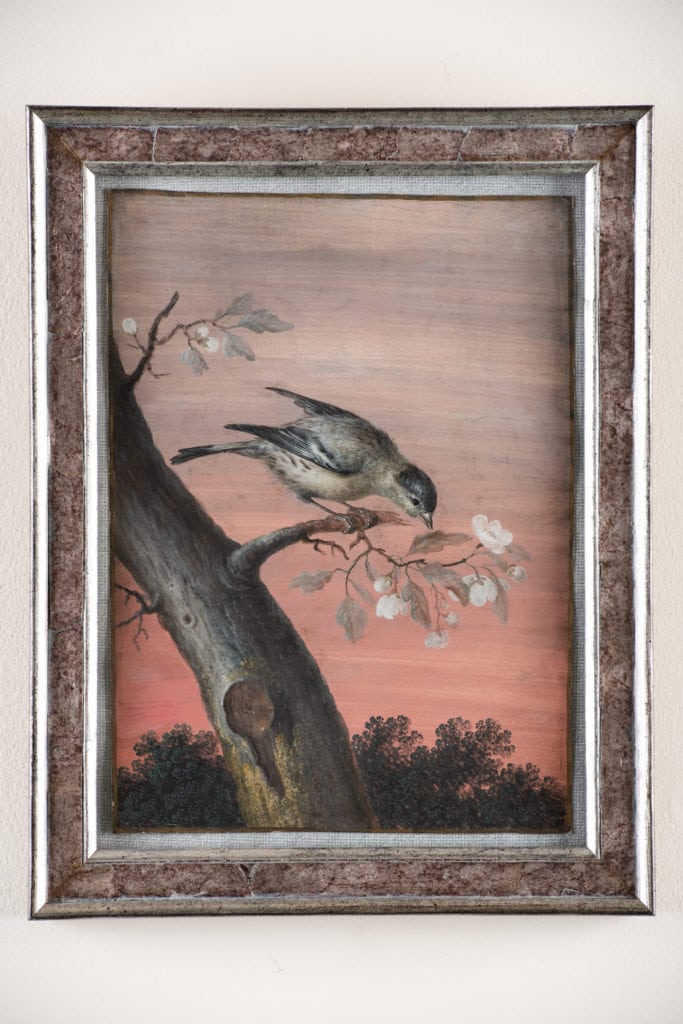

- Christoph Ludwig Agricola (German, 1667-1719), “Untitled”, Eurasian Siskin (Spinus spinus), Gouache on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Christoph Ludwig Agricola (German, 1667-1719), “Untitled”, Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), Gouache on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Christoph Ludwig Agricola was a German painter known for his exceptional fidelity to nature, particularly his skillful representation of weather anomalies such as thunderstorms. He largely painted many cabinet pictures – small paintings intended for the enjoyment of private collectors – so named for the small rooms or “cabinets” in which such works were often displayed. He is known to have created multiple paintings of birds such as this male Eurasian Siskin and male Common Kingfisher.

Jean-Francois de Galaup, comte de La Perouse

Jean-Francois de Galaup, comte de La Perouse (French, 1741-1788), “Black Bird of Port des Francais, No. 22”, Varied Thrush (Ixoreus naevius) taken in Lituya Bay, Alaska (a.k.a. Port des Français), From: “Charts And Plates To La Perouse’s Voyage”, Engraving on paper, c. 1798-1799, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Eleazer Albin

Eleazar Albin (English, 1690-1742), “Anas Arctica, The Puffin or Coulternel, 79”, Atlantic Puffin (Fratercula arctica), Hand-colored engraving on paper, c. 1734, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

This print of an Atlantic Puffin is from the first French edition of Histoire Naturelle des Oiseaux or The Natural History of Birds which was published in The Hague in Pierre de Hondt in 1734 by Eleazer Albin. Note the abnormally upright posture. This is not how this species stands in life and likely indicates that the image was painted from a stuffed specimen.

Mark Catesby

Mark Catesby (English, 1683-1749), “Red Winged Starling; Broad-leaved Candle-berry Myrtle, T. 23”, Red-winged Blackbird (Agelaius phoeniceus), From: “The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands”, Hand-colored engraving on paper, c. 1731-1775 (Edition unknown), On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Mark Catesby was an English naturalist who studied the plants and animals of the New World. He published the Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands between 1729 and 1747. This was the first published account of the flora and fauna of North America. It included 220 plates depicting birds, mammals, reptiles, amphibians, fish, insects, and plants. This plate illustrates a male Red-winged Blackbird in a courtship display – a widespread species in North and Middle America.

Barbara Regina Dietzsch

Barbara Regina Dietzsch (German, 1706-1783), “Untitled”, Scissor-tailed Flycatcher (Tyrannus forficatus), Aquarelle and gouache on paper, c. 1770, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Barbara Regina Dietzsch was a member of an important family of painters, engravers, and musicians that flourished in Nuremberg in the German state of Bavaria during the eighteenth-century. Dietzsch was particularly known for her exquisite renderings of flowers, fruit, insects, and birds. With exceptional mastery and stylistic power, Dietzsch overcame contemporary estimations of women’s inferiority in the field of art, creating watercolors of distinctive splendor.

This painting seems to depict a Scissor-tailed Flycatcher, a species that breeds in the southern United States and northern Mexico and winters to Central America. Birds from the Americas, particularly those as beautiful as the Scissor-tailed Flycatcher would have been coveted as specimens. The truncated tail on this bird may indicate that it is a juvenile or that the typically long tail was damaged in transport to Germany.

Ernst Friedrich Carl Lang

- Ernst Friedrich Carl Lang (German, 1748-1782), “Untitled”, Bohemian Waxwing (Bombycilla garrulus) on a branch, Gouache on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Ernst Friedrich Carl Lang (German, 1748-1782), “Untitled”, European Goldfinch (Carduelis carduelis) on Thistle, Gouache on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

These beautiful bird studies depicting a Bohemian Waxwing and a European Goldfinch are rare examples of the work of Ernst Friedrich Carl Lang. Lang moved to Nuremberg in 1755 and was a pupil of the famed natural history painter Barbara Regina Dietzsch (see painting above), who specialized in the depiction of flowers, birds, and insects. Dietzch’s influence can be seen in Lang’s delicacy of brushstrokes and the composition’s sophistication. The lack of background detail gives the work a simplicity that fully appreciates the bird’s plumage coloring. Moreover, the color of these enchanting birds’ feathers is echoed in the shade of the background.

Sarah Stone

- Sarah Stone (English, 1760-1844), “Cayenne Warbler (Motacilla Cayona)”, Blue Dacnis (Dacnis cayana), adult male, Ink and watercolor on paper, 1781, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Sarah Stone (English, 1760-1844), “Senegal Parrot, West Africa”, Senegal Parrot (Poicephalus senegalus senegalus), Watercolor, ink and gouache heightened with gum arabic on laid paper, c. 1777-1806, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Sarah Stone (English, 1760-1844), “Cashew Curassow (Crax Pauxi)”, Helmeted Curassow (Pauxi pauxi), Watercolor, ink and gouache heightened with gum arabic on laid paper, 1789, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Sarah Stone (English, 1760-1844), “Falco Pygargus”, Montagu’s Harrier (Circus pygargus), adult female, Watercolor and gouache on paper, c. 1777-1806, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Sarah Stone is synonymous with the Lever Museum (also known as the Leicester House), a significant cultural phenomenon of 18th-century London. Sir Ashton Lever employed this fine female artist to record specimens and ethnographic material brought back by British expeditions to Australia, the Americas, Africa, and the Far East in the 1780s and 1790s- perhaps the most significant being Captain Cook on his round-the-world voyages. Stone’s meticulous paintings provide a unique record of the discoveries made by sailors and naturalists onboard British survey ships and the new colonies. They were also incredibly beautiful and technically accurate.

Sarah’s drawings’ importance lies in the fact that she not only recorded so many new scientific discoveries for the first time, but she also documented them while they were still under one roof. Throughout her nearly 30-year career, she was extremely prolific, painting over 1,000 watercolors of mounted birds, mammals, fishes, insects, reptiles, shells, minerals as well as ethnographic artifacts. She was known to sign and date many of her watercolors. Lever either purchased or was gifted the first specimens ever recorded or known to science in several fields. Unfortunately, his museum no longer exists; contents dispersed in 1806. Many of its examples have been lost forever. As a result, Stone’s paintings act as aesthetically beautiful works of art and provide an essential record of specimens used by naturalists in the age of Linnaeus, some of which are now extinct.

Only about 900 of her paintings exist today. However, they were often requested to be engraved for illustrations in natural history publications. By 1789 she was well known in London both to the public who visited the famous Lever museum as well as to the experts of the day. They were interested in natural history and everything to do with the voyages of Captain Cook. While she painted all of her subjects with a keen eye, it was thought that her drawings of birds, in particular, showed a considerable amount of technical skill. She was self-taught, and her talents were clearly innate. However, her father was a fan painter, working somewhat in the style of the French Rococo artist Antoine Watteau. Fan painting requires superb and accurate coloring skills, and map colorists often did this intricate and delicate job. As a child, Sarah learned to use local and even household ingredients for her pigments – brickdust, or the juice of leaves or flower petals. Later, Sarah used these skills in selecting the colors prompting her to work with colors that she considered permanent: Chinese white, ivory black, burnt sienna, Vandyke brown, yellow ochre, chrome lemon and yellow, light orange cadmium, vermilion, carmine, madder lake, Veronese green, sap green, cobalt, ultramarine and Prussian blue. She also employed gum Arabic to gouache powders, and she learned to mix watercolor paint and add white for opacity and highlights. Her consistent techniques only enhanced the appearance of her artwork.

Stone diligently recorded and was highly faithful when she portrayed her subjects, painstakingly documenting the models in front of her. Had she employed more artistic license, some of her forms would have come across more naturalistic, but she stayed true to how the taxidermists arranged the subjects. Her works, therefore, can also be read as a historical analysis of 18th century taxidermic practices. When Sarah provided tree branches as part of her background, as we see in this fine example, they were distinctive hallmarks of her work. They were nearly depicted as pale grey or silver, like silver birch bark, with a little lichen, very delicately traced.

It is clear to see how influential Sarah Stone is to the history of natural history illustration and the tremendous skill required to paint such diverse subjects, both zoological and ethnographical. We can admire this piece’s delicacy of the brushwork and her touch when it comes to color. The result has a brilliance and sheen that hardly reads as if it dates from the 18th century.

Samuel Howitt

- Samuel Howitt (English, 1765-1822), “Hobby, Falco Subbuteo (Juvenile)”, Eurasian Hobby (Falco subbuteo), Pen and ink, watercolor and pencil on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Samuel Howitt (English, 1765-1822), “Indian Woodpecker”, Waved Woodpecker (Celeus undatus), Pen and ink and watercolor on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Samuel Howitt (English, 1765-1822), “Spotted Ruff-Bird”, Spotted Puffbird (Bucco tamatia) , Pen and ink and watercolor on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

As a young man, Samuel Howitt had a very carefree nature. His lifestyle brought financial obligations, which he tried to meet as an artist. In reaction to his stable Quaker upbringing, Howitt was an active participant in the thriving London social scene of gambling, hunting, fishing, and sporting. He was not alone in his rounds of London’s drinking houses. His brother-in-law, the noted caricaturist and watercolorist, Thomas Rowlandson, joined him. Samuel’s marriage to Rowlandson’s sister was not a success, and apparently, his passion for fishing and sporting excursions led to their separation.

Howitt’s initial artistic efforts were somewhat crude, but his natural talents quickly and skillfully progressed to a remarkable degree. He exhibited at the Royal Academy between 1783 and 1815. His quick fretted outlines reflect the influence of Rowlandson. He was prolific in oil and watercolor, and as a printmaker, and his lighthearted works appeared in numerous sporting and other publications. In 1808, he provided illustrations for The Angler’s Manual. In 1812, seventy of his images appeared in the British Sportsman, and later a large group appeared in The Old Sporting Magazine.

However, Howitt’s best-known work is Oriental Field Sports, a collection of forty beautiful and dramatic aquatints drawn by Howitt after the original sketches of his friend Captain Thomas Williamson. The book’s primary purpose was to explicate and illustrate the excitement and peculiarities of Indian game hunting, both big and small. Williamson had explored Bengal’s innermost regions in search of the exotic Asian prize, and from his sketches, Howitt produced some of the most prized images of big-game hunting.

His habit of drawing animals from life at the Tower of London was the basis of the 1811 A New Work of Animals, fifty-six carefully executed designs based on the fables of Aesop. Likely, the Tower of London was also the source for many of the watercolors of animals and birds here presented. However, Bullock’s notation on some would indicate that he also used specimens from this renowned dealer in animal skins.

The companion album to the collection is now in London’s Natural History Museum and forms part of the famed banker’s holdings, Baron Rothschild of Tring. Rothschild was a keen amateur scientist and, from the age of seven, started collecting specimens. He founded the Zoological Museum at Tring, opening it to the public in 1892. Moreover, he wrote several articles on ornithology and held distinguished positions as Trustee of the Natural History Museum, Chairman of the British Ornithologists’ Club (1913-1918), and President of the British Ornithologist’s Union (1923-1928).

It is not certain when the two albums of Howitt’s drawings were divided, and thus difficult to establish a definite provenance to the Rothschild collection for the set pictured here. However, they are fine examples of one of the leading natural history painters of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries.

19th Century

John Abbott

- John Abbot (American, 1751-1840), “White Throated Finch”, White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis), Watercolor on paper, c. 1823, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Abbot (American, 1751-1840), “Fox Colored Sparrow”, Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca), Watercolor on paper, c. 1823, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

This collection of striking and distinctive bird watercolors is of exceptional importance in the field of American natural history, and of Georgia wildlife in particular because they are some of the earliest American ornithological watercolors. Abbot’s oeuvre has only recently been recognized and elevated to the rank of such better-known predecessors and contemporaries as Mark Catesby, Alexander Wilson, and John James Audubon.

- Nicolas Huet II (French, 1770-1828), “Pl. 508. Martin pecheur lazuli.”, Lazuli Kingfisher (Todiramphus lazuli), female; Distribution: S Moluccas: Seram, Ambon and Haruku., Watercolor and pencil on paper, c. 1820-1839, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Alexander Wilson (Scottish-American, 1766-1813), “Plate 26: 1. Carolina Parrot. 2. Canada Flycatcher. 3. Hooded F. 4. Green, black-capt F.”, Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis); Canada Warbler (Cardellina canadensis); Hooded Warbler (Setophaga citrina); Wilson’s Warbler (Cardellina pusilla), From: “American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States”, Hand-colored copper plate engraving on paper, 1829, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Alexander Wilson (Scottish-American, 1766-1813),”Plate 22: 1. Swamp Sparrow. 2. White-throated Sp. 3. Savannah Sp. 4. Fox-coloured Sp. 5. Loggerhead Shrike”, Swamp Sparrow (Melospiza georgiana); White-throated Sparrow (Zonotrichia albicollis); Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis); Fox Sparrow (Passerella iliaca); Loggerhead Shrike (Lanius ludovicianus), From: “American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States”, Hand-colored copper plate engraving on paper, 1829, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Alexander Wilson (Scottish-American, 1766-1813), “Plate 69: 6 Pied Duck. 2 Red-breasted Merganser. 4 American Widgeon Male. 5 Female Snow Goose. 3 Blue Bill or Scaup Duck. 1 Hooded or Crested Merganser.”, Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius) – male; Red-breasted Merganser (Mergus serrator) – male; American Wigeon (Mareca americana) – male; Snow Goose (Anser caerulescens) – blue phase; Greater Scaup (Aythya marila) – male; Hooded Merganser (Lophodytes cucullatus) – male”, From: “American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States”, Hand-colored copper plate engraving on paper, 1829, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Alexander Wilson (Scottish-American, 1766-1813), “Plate 56: 1. Esquimaux Curlew. 2. Red backed Snipe. Semipalmated S. 4. Marbled Godwit”, Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis); Dunlin (Calidris alpina); Willet (Tringa semipalmata); Marbled Godwit (Limosa fedoa)”, From: “American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States”, Hand-colored copper plate engraving on paper, 1829, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Alexander Wilson (Scottish-American, 1766-1813),”Plate 44 1. Passenger Pigeon. 2. Blue-mountain Warbler. 3. Hemlock W: 44.”, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius); Blue-winged Warbler (Vermivora cyanoptera); Pine Warbler (Setophaga pinus), From: “American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States”, Hand-colored copper plate engraving on paper, 1829, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate CCCXXVI (326): Gannet”, Northern Gannet (Morus bassanus), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate LXI (61): Passenger Pigeon”, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate XXI (21): Mockingbird”, Northern Mockingbird (Mimus polyglottos), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate XXVI (26): Carolina Parrot”, Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate LXVI (66): Ivory-billed Woodpecker”, Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), From: “The Birds of America”,Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate CCCCII (402): Black-throated Guillemot, Nob-billed Auk, Curled-crested Auk, Horned-billed Guillemot”, Ancient Murrelet (Synthliboramphus antiquus), Kittlitz’s Murrelet (Brachyramphus brevirostris), Least Auklet (Aethia pusilla), Crested Auklet (Aethia cristatella), Rhinoceros Auklet (Cerorhinca monocerata), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Webber (English, 1751-1793), “Captain Cook – A View of Snug Corner Cove, in Prince William’s Sound”, Panoramic View Prince William Sound, Alaska, Engraving on paper, 1785, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Prideaux John Selby (English, 1788-1867), “Gull Billed Tern, Sandwich Tern, Plate LXXXVIII”, Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica); Sandwich Tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Hand-colored engraving on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Prideaux John Selby (English, 1788-1867), “A Little Auk”, Dovekie (Alle alle), Pen and ink and watercolor on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Prideaux John Selby (English, 1788-1867), “Untitled”, Common Gull in Winter Plumage (Larus canus), Pen, ink and watercolor on paper, n.d., On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Prideaux John Selby (English, 1788-1867), “Untitled”, Sandwich Tern (Thalasseus sandvicensis), Pen and ink and watercolor on paper, c. 1815-1833, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Edward Lear (English, 1812-1888), “Numidian Demoiselle. Anthropoides Virgo; (Vieill:) (Volume 4, Plate 272)”, Demoiselle Crane (Anthropoides virgo), From: “The Birds of Europe”, Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c.1837-1837, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Elizabeth Gould (English, 1804-1841) Falco rufipes. (Bechst). Red footed Falcon.”, Red-footed Falcon (Falco vespertinus); female (top), male (bottom left), juvenile (bottom right), Printer’s proof lithograph on paper, c.1837-1837, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Elizabeth Gould (English, 1804-1841), “Red Footed Falcon.”, Falco rufipes. (Bechst) (Volume 1, Plate 23) Red-footed Falcon (Falco vespertinus); female (top), male (bottom), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c. 1832-1837, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Aprosmictus Scapulatus. (King Lory, Volume 5, Plate 17)”, Australian King-Parrot (Alisterus scapularis); male (left and front), female (right and rear), Hand-colored lithograph, c.1840-1848, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Eucephala Smaragdocaerulea, Gould. (Green and Blue Sapphire; Volume 5, Plate 331)”, Violet-capped Woodnymph (Thalurania glaucopis), Hand-colored lithograph with gold leaf on paper, c. 1849-1861, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- William Hart (Irish-English, 1823-1894), “Lophornis Pavoninus, Salv. & GODM. (Roraima Coquette; Suppliment, Plate 36), Peacock Coquette (Lophornis pavoninus), Hand-colored lithograph with gold leaf on paper, c. 1880-1887, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Eriocnemis Lugens, Gould. (Hoary Puff-leg; Volume 4, Plate 282”, Hoary Puffleg (Haplophaedia lugens), Hand-colored lithograph with gold leaf on paper, c. 1849-1861, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Orthorhynchus Cristatus. (Blue-Crest.; Volume 4, Plate 205)”, Antillean Crested Hummingbird (Orthorhyncus cristatus), Hand-colored lithograph with gold leaf on paper, c. 1849-1861, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Untitled”, Willow Warbler (Phylloscupus trochilus), Pencil and Watercolor, c.1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Untitled”, Little Tern (sternula albifrons); adult at nest and in flight with chicks, Watercolor on paper, c. 1860-1865, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Sternuyla Minuta. (Little Tern; Volume 5, Plate 73)”, Little Tern (Sternula albifrons); adult at nest and in flight with chicks, Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c. 1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Untitled”, Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps crisatus), Watercolor on paper, 1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Podiceps Cristatus, Linn. (Great-crested Grebe; Volume 5, Plate 38)”, Great Crested Grebe (Podiceps cristatus), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c.1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Joseph Wolf (German, 1820-1899) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Falco Aesalon, Linn. (Merlin; Volume 1, Plate 19)”, Merlin (Falco columbarius); male top with a freshly killed Yellowhammer, (Emberiza citrinella) with female and nestlings below, Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c.1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Pica Caudata. (Magpie; Volume 3, Plate 63)”, Eurasian Magpie (Pica pica), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c. 1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & Henry Constantine Richter (English, 1821-1902), “Mergulus Alle. (Little Auk; Volume 5, Plate 50)”, Dovekie (Alle alle); juvenile (left) and adult in breeding plumage (right), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c. 1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Édouard Traviès (French, 1809-1876), “Untitled”, Pl. 24.: Épervier commun (Falco nisus, Linn.) Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus), Watercolor on black pencil lines on paper, 1846, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Charles Barney Cory (American, 1857-1921), “Camptolaemus Labradorius. (Plate 11; Labrador Duck)”, Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius), Hand-colored chomolithograph on paper, c.1883, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Robert Havell Jr. (English, 1793-1878), “Bird of Prey”, Red-tailed Hawk (Buteo jamaicensis), immature in stoop hunging over the Hudson River, Oil on canvas, 1851-1859, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

20th Century

- Walter Rothchild (English, 1868-1937), “Extinct Birds, Plate 36. Camptolaemus Labradorius”, Labrador Duck (Camptorhynchus labradorius), Chromolithograph on paper, c. 1907, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

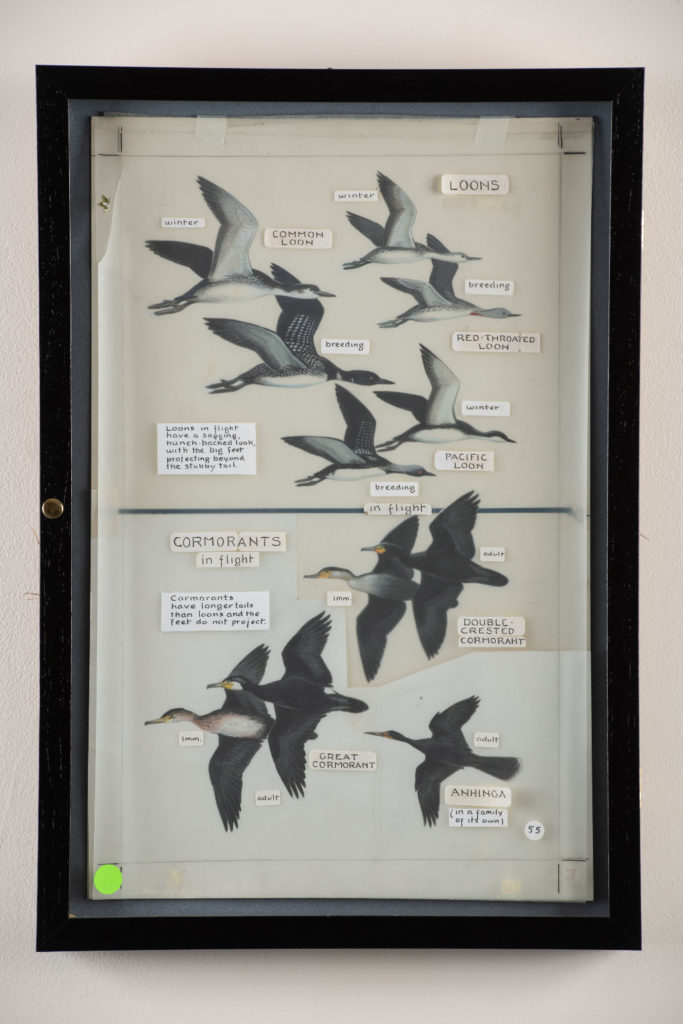

- Roger Tory Peterson (American, 1908-1996), “Loons in Flight; Cormorants in Flight”, Common Loon (Gavia immer) in winter and breeding plumage; Red-throated Loon (Gavia stellata) in winter and breeding plumage; Pacific Loon (Gavia pacifica) in winter and breeding plumage; Great Cormorant (Phalacrocorax carbo) immature and adult; Double-crested Cormorant (Phalacrocorax auritus) immature and adult; Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga) adult. Brandt’s Cormorant (Phalacrocorax penicillatus) and Pelagic Cormorant (Phalacrocorax pelagicus), Gouache, watercolor, pencil and ink on board with overlay on paper, c.1990, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Roger Tory Peterson (American, 1908-1996), “Eiders”, Common Eider (Somateria mollissima), King Eider (Somateria spectabilis), Steller’s Eider (Polysticta stelleri), Spectacled Eider (Somateria fischeri) each shown in order: adult male and female in flight, then adult female, immature male, and adult male sitting, Gouache, watercolor pencil, and ink on paperboard cut-outs, c. 1993, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

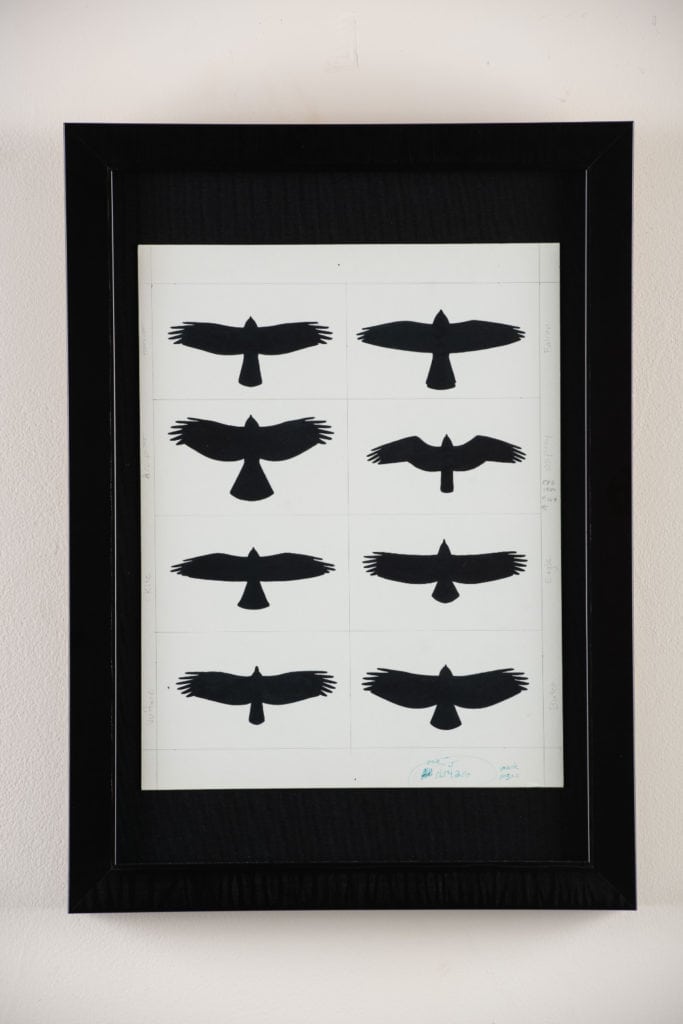

- Roger Tory Peterson (American, 1908-1996), “Eagles, Osprey Overhead”, Bald Eagle (Haliaeetus leucocephalus), adult and juvenile; Golden Eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), agule and juvenile; Osprey (Pandion haliaetus), adult, Gouache, watercolor, and pencil on board, c.1980, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Roger Tory Peterson (American, 1908-1996), “Raptor and Vulture Silhouettes in a Full Soar Posture from Below”, Harrier; Accipiter; Kite; Vulture; Falcon; Osprey; Eagle; Buteo, Ink on paper, c. 1980, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John A. Gwynne (American, 20th century), “Forest Falcons of Central Brazil”, Laughing Falcon (Herpetotheres cachinnans), Barred Forest-Falcon (Micrastur ruficollis), Collared Forest-Falcon (Micrastur semitorquatus), Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper, 2006, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John A. Gwynne (American, 20th century), “Open Country Hawks of Central Brazil”, Zone-tailed Hawk (Buteo albonotatus), Swainson’s Hawk (Buteo swainsoni), White-tailed Hawk (Geranoaetus albicaudatus), Pencil, watercolor and gouache on paper, 2006, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Guy Adwill Tudor III (American, 1934-), “Plate 23. Cuckoos and Jays”, Yellow-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus americanus), Dark-billed Cuckoo (Coccyzus melacoryphus), Gray-capped Cuckoo (Coccyzus lansbergi), Dwarf Cuckoo (Coccycua pumila), Striped Cuckoo (Tapera naevia naevia), Pavonine Cuckoo (Dromococcyx pavoninus pavoninus), Pheasant Cuckoo (Dromococcyx phasianellus phasianellus), Little Cuckoo (Coccycua minuta minuta), Squirrel Cuckoo (Piaya cayanamehleri), Black-bellied Cuckoo (Piaya melanogaster melanogaster), Rufous-winged Ground-Cuckoo (Neomorphus rufipennis), Black-collared Jay (Cyanolyca armillata meridana), Black-chested Jay (Cyanocorax affinis affinis), Green Jay (Cyanocorax yncas guatimalensis), Violaceous Jay (Cyanocorax violaceus violaceus), Cayenne Jay (Cyanocorax cayanus), Gouache, watercolor, ink on art board, c. 1989-2003, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- David Beadle (American, 1961-), “Savannah Sparrow”, Savannah Sparrow (Passerculus sandwichensis) – various ages and subspecies, Watercolor on paper, 1996, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- David Beadle (American, 1961-), “Snow/McKay’s Bunting”, Snow Bunting (Plectrophenax nivalis) and McKay’s Bunting (Plectrophenax hyperboreus), males, females, and immature/juveniles, Watercolor on paper, 1996, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- David Beadle (American, 1961-), “Savannah Sparrow Head details”, Savannah Sparrow; “Large-billed” Savannah Sparrow; “Belding’s” Savannah Sparrow; “Ipswich” Savannah Sparrow, Watercolor on paper, 1996, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- David Beadle (American, 1961-), “Spizella Heads”, Chipping Sparrow; Clay-colored Sparrow; Brewer’s Sparrow; American Tree Sparrow; Field Sparrow; Black-chinned Sparrow, Pen and ink on paper, 1996, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- David Beadle (American, 1961-), “Savannah Sparrow”, Passerculus s. sandwichensis; Cow Parsnipip – Heracleum lanatum, Pen and ink on paper 1996 On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Great Auks

- George Edwards (English, 1694 – 1773), “Northern Penguin. 147”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored engraving on paper, c.1743, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Giuseppe Maria Terreni (Italian, 1739-1811), “Penguino Dell’ America Settentrionale (North American Penguin)” Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c.1763, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Prideaux John Selby (English, 1788-1867), “Great Auk. Plate LXXXII”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored engraving on paper, c.1819-1834, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Saverio Manetti (Italian, 1723-1785), Drawn and etched by Violante Vanni and Lorenzo Lorenzi, “Pinguino maggiore. Alca major. CDLXXXXVII (497)”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored engraving on paper, c.1767-1776, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- John Gould (English, 1804-1881) & William Hart (English, 1823-1894), “Alca Impennis. (Great Auk; Volume 5, Plate 46)”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored lithograph on paper, c.1862-1873, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Charles Barney Cory (American, 1857-1921), “Alca Impennis. (Plate 5; Alca Impennis, Great Auk)”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Hand-colored chromolithograph on paper, c.1883, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

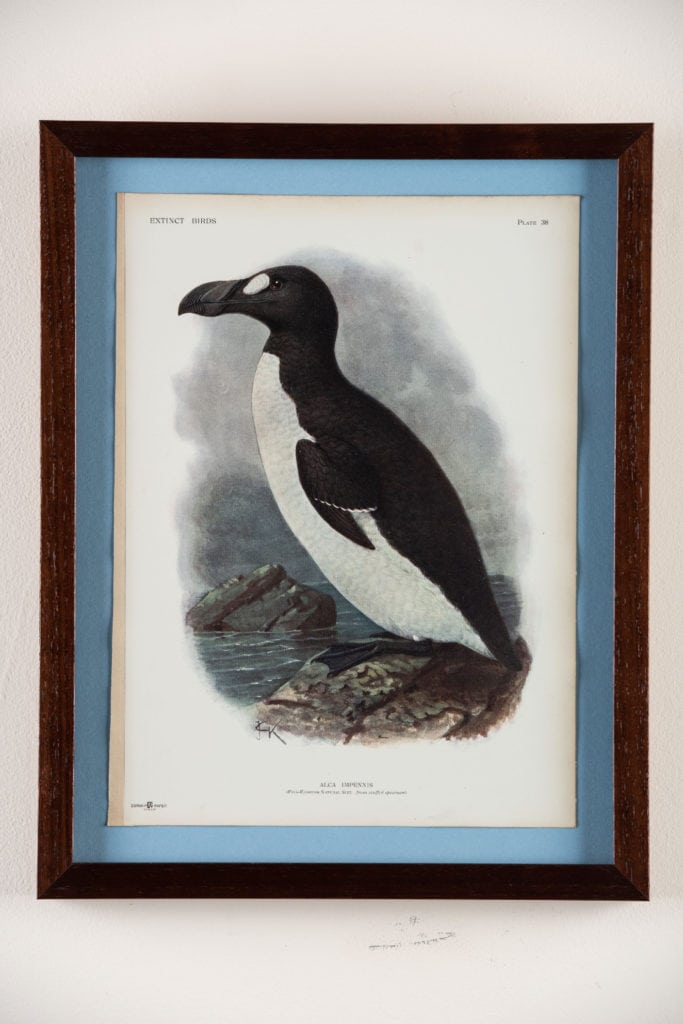

- Walter Rothschild (English, 1868-1937), “Extinct Birds, Plate 38, Alca Impennis”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Chromolithograph on paper, c.1907, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- Raymond Harris-Ching (New Zealand, 1939-), “The Great Auk imagined off Eldsey Island”, Great Auk (Pinguinus impennis), Offset lithograph on paper, 1995, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Passenger Pigeon

- John James Audubon (American, 1785-1851), “Plate LXI (61): Passenger Pigeon”, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), From: “The Birds of America”, Hand-colored aquatint engraving on paper, c. 1827-1838, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- “Feather of extinct Passenger Pigeon, male (left) female (right)”, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius), On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

“Men still live who, in their youth, remember pigeons; trees still live who, in their youth, were shaken by a living wind. But a few decades hence only the oldest oaks will remember, and at long last only the hills will know.”

—Aldo Leopold, “On a Monument to the Pigeon,” 1947

Above you can see the feathers from both a male and female Passenger Pigeon, along with Audubon’s “Plate LXI (61): Passenger Pigeon, Passenger Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius)” which features the bird. At one point in time, Passenger Pigeons in North America numbered in the billions. There are numerous historical records of flocks of Passenger Pigeons so large that they blocked out the sun as they moved across the sky. While there are many factors that led to their extinction, over-hunting and a lack of genetic diversity within the species are the most commonly cited causes of the Passenger Pigeon’s demise.

Eskimo Curlew

- Thomas Hewes Hinckley (American, 1813-1896), “Untitled”, Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis), Oil on Canvas, 1874, On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

- “Feather of an extinct Eskimo Curlew”, Eskimo Curlew (Numenius borealis), On loan from the collection of Dr. Michael and Elyn Stubblefield

Above you will find a single feather from an Eskimo Curlew accompanied by Thomas Hewes Hinckley’s oil painting of the bird. While this species has not been declared extinct officially, it has not been sighted since 1963. It is believed that the bird was once among the most common shorebirds in North America, numbering in the millions. Like the Passenger Pigeon, the Eskimo Curlew was a common target for hunters. This certainly contributed to the bird’s decline, but is not the only reason to blame. As prairies were plowed over by humans, the primary food source of the Eskimo Curlew, the Rocky Mountain Grasshopper, disappeared. Both over-hunting and a loss of habitat contributed to the endangerment of this once-abundant species.