Person, Place, Thing: Paintings by Women Artists in Brenau’s Collection

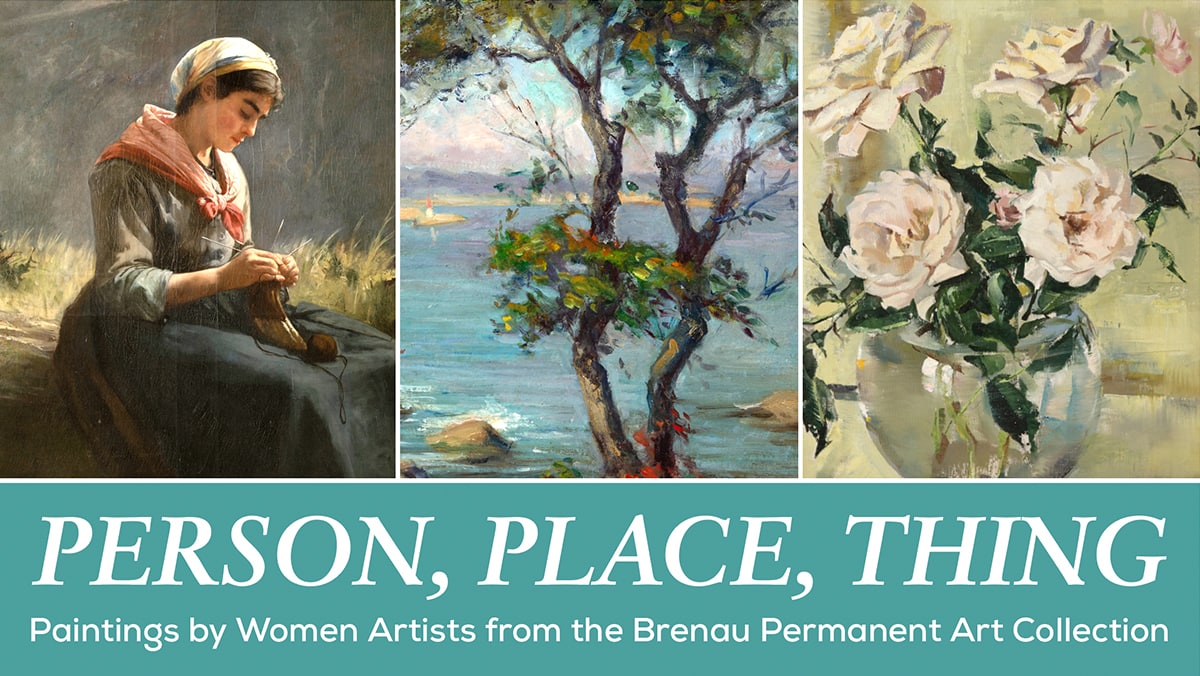

The works in this exhibition exist within a rich tradition of historical genre painting – landscape, portraiture, and still life. While diverse in their application, these genres have existed in some form as far back as people have been making art. Women artists have long been involved in these traditional painting specializations, but have categorically received less recognition than their male counterparts. This exhibit highlights exceptional women artists from the 19th and 20th centuries from within Brenau’s Permanent Art Collection and acknowledges their contribution to the genres of landscape, portraiture, and still life.

The works tied to “place” within this exhibition represent the genre of landscape, which offers the opportunity for incredible variety. Typically, landscape art depicts natural settings that can exist as their own subject or as the background for something figurative. Within this exhibition, the places represented demonstrate the versatility of the genre. Alice Frye Leach takes us to a quaint village dwelling in Italy, while Marguerite Stuber Pearson shows us a soothing slice of American coastal life. In between, we may find ourselves in bustling towns and the English countryside. The variety of styles and places included in the exhibition demonstrate the ability of landscape to be truly transportive while showcasing the contributions of women to the genre.

The “people” represented in this exhibition demonstrate two major trends of portraiture – traditional portraiture focuses predominantly on the sitter’s face, while genre portraiture may contextualize the sitter within a setting. In Elizabeth Klumpke’s Catinou Knitting, viewers get a glimpse of the sitter engaged in a task while ignoring our gaze. Dorothy Ochtman’s Young Man, in contrast, focuses on the bust of the sitter while he stares out at us. Whether through a strong and direct gaze, a mysterious aloofness, or an engaging smile, portraits have a unique ability to engage viewers and the works selected for this exhibition are no exception.

As a genre, still life has origins in Ancient Greco-Roman art – but it emerged in Western painting as a popular specialization by the 16th century. The subject matter for a still life is typically inanimate – including easily obtained items such as food, flowers, natural objects, or household items. However, the artist’s ability to arrange and manipulate the grouping of these objects into a composition elevates the potential for still life works to be particularly interesting or symbolic. Consider the works around the gallery depicting flowers. No two works are the same – from Gertrude Martin Tonsberg’s Pansies to Mae Bennett Brown’s Zinnias, from Nan Greacen’s glass bowl to Ellen Whales Hutchinson’s varied vases – the still life genre allows the artist great freedom in representing their subject. The still lifes, or “things”, included in this exhibition demonstrate a mastery of the genre by women in the Brenau Collection.

The works included in this exhibition represent a selection of exceptional women featured in Brenau University’s Permanent Art Collection. The thread tying them together – person, place, and thing – reflects the significant historical contribution of women to these professional specializations within painting. One piece that encapsulates these concepts completely is Emma Fordyce McRae Smith’s Still Life/Portrait. This piece includes a traditional still life featuring a painted portrait of a woman in the background – Smith’s way of demonstrating her prowess across multiple genres. Women really can do it all.

Click on thumbnail to enlarge image.

- Ida Pulis Lathrop (American, 1859–1937), “Apple Blossoms”, n.d., Oil on canvas, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Dorothy Ochtman (American, 1892-1971), “Young Man”, n.d., Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Susan Ricker Knox (American, 1874 – 1959), “El Pico” C. 1987 Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Anne Carleton (American, 1878–1968), “Lighthouse”, n.d., Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Emma Fordyce McRae Smith (American, 1887-1974), “Still Life/Portrait”, n.d., Oil on canvas over masonite, Gift of Fred Bentley, Sr.

- Ethel Paxson (American, 1885-1982), “Lilacs and Blue Velvet”, n.d., Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Gertrude Martin Tonsberg (American, 1902-1973), “Pansies” n.d., Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Mae Bennett Brown (American, 1887-1973), “Zinnias”, n.d., Watercolor on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Eleanor Curtis Ahl (American, 1875-1953), “The Old Farm”, n.d., Watercolor on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Mary Helen Potter (American, 1862 – 1950), “The Kimono”, n.d., Watercolor on paper, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Ethel Elizabeth Foster (American, 1873 – 1968), “Mixed Bouquet”, n.d., Oil on canvas, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Nan Greacen (French-American, 1909-1999), “White Roses in a Glass Bowl”, n.d., Oil on canvas, Gift of Fred Bentley, Sr.

- Bessie Jeanette Howard (American, 1890-1962), “New England Summer”, 1935, Oil on canvas, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Mary Bigelow (American, 1886-1969), “Barnstable, Cape Cod”, n.d. , Oil on board, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Marguerite Stuber Pearson (American, 1898-1978), “Coastal Scene-Summer”, n.d., Oil on canvas board, Gift of Fred Bentley, Sr.

- Alice Frye Leach (American, 1857-1942), “Perugia”, 1927, Oil on board, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

- Ellen Whales Hutchinson (American, 1867-1937), “Spring Flowers”, n.d., Oil on canvas, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke (American, 1856 – 1942), “Catinou Knitting”, 1887, Oil on canvas, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

Anna Elizabeth Klumpke (1856-1942)

Encouraged by an independent, educationally oriented mother, Klumpke was a copyist in the Luxembourg Museum and studied at the Academie Julien in Paris, where she enjoyed an education guided by the concept that women artists could compete with their male counterparts. In her memoirs of 1940, she cites a most influential moment in her childhood: receiving the gift of a Rosa Bonheur doll. Her admiration of Bonheur, the French painter of animals, led her to paint the aging woman’s portrait – which is considered a companion piece to her portrait of leading suffragist, Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The time that Klumpke spent with Bonheur in By, France, subsequently led to her commitment to being the older artist’s lady companion and biographer. After Bonheur’s death, Klumpke was entrusted with the dispensation of the artist’s estate. The Bonheur chateau was a convalescent home for the wounded during World War I, an established neutral zone protected by an American flag fashioned out of the material of Bonheur’s blouse.

Catinou Knitting (Catinou may be the name of the sitter) was executed during Klumpke’s residency in Paris, after her educational experiences at the Academie. She dedicated this scene of a French peasant girl to her father. Its ambitious size and delicacy of form reflect both the independent spirit of the artist and her training in the French academic tradition.

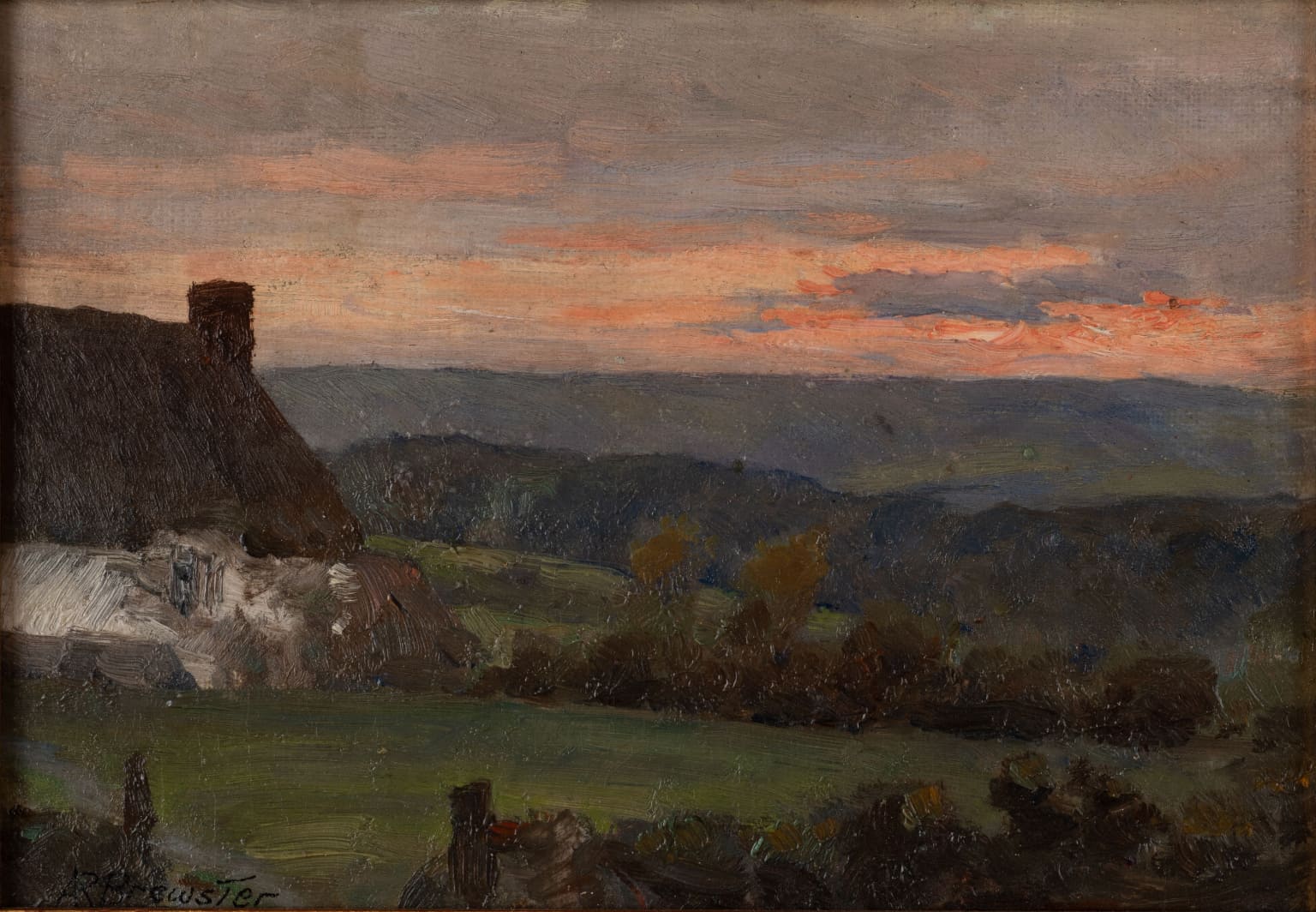

Anna Mary Richards Brewster (American, 1870-1952), “Sierra, Clovelly”, n.d., Oil on canvas, Gift of Alan and Louise Sellars

Anna Richards Brewster (American, 1870-1952)

Anna Richards Brewster, daughter of American marine-scape painter William Trost Richards,studied under John LaFarge and William Merritt Chase in New York, and also trained at the Academie Julien. During her early career as an illustrator, Brewster collaborated on a book of sonnets, entitled “Letter and Spirit of 1898”, with her mother, Anna Matlack Richards. During her later career, Brewster traveled extensively in Europe, the eastern United States and Northern Africa.

From 1895 to 1905, Brewster painted professionally in London. In the beginning of this period, she spent approximately a year in the picturesque fishing village of Clovelly in Devon. Sierra Clovelly was executed during this most prolific stage in Brewster’s long career. Her husband, Shakespearean scholar William Tenney Brewster, published four volumes of material on Anna’s work. He detailed her particular landscape painting method of beginning at the top of the canvas and allowing the tone of the sky to set the color scheme of the areas below. At the time of her death, she left behind more than two thousand sketches.