GRL PWR: Women Artists in the Brenau Collection

GRL PWR

Curator’s Statement

Since its inception, Brenau Galleries has brought extraordinary exhibitions from prominent women artists and unique group exhibitions to the campus of its historic Women’s College and the Gainesville community. These exhibitions helped to distinguish Brenau University as a destination for arts and culture in Northeast Georgia. What is lesser-known, perhaps, is the fact that Brenau’s Permanent Art Collection houses work by some of the most celebrated women artists of the 20th and 21st centuries including Louise Nevelson, Louise Bourgeois, Helen Frankenthaler, Beverly Buchanan, Lynda Benglis, and Kiki Smith. When choosing works for this exhibition, I wanted to honor these women who are sometimes overlooked in favor of our male-dominated Pop Art collection, largely built through Brenau’s relationship with Leo Castelli. GRL PWR shifts the spotlight to the women of the collection, who are just as significant in their own rite.

The artists included in this collection of paintings and works on paper represent nearly a century of creative work and frequently defy categorization. Though disparate in their choices of medium and subject matter, boldness and innovation are the common threads that bind these women together. Many of the artists in this exhibition used their work to address gender in various ways, while others redefined the role of women in art by claiming their right to create in a space traditionally monopolized by men. Marisol used humor and mimicry to reject the prescribed social roles of women that prevailed in the years post-World War II. Louise Bourgeois chose to explore the female form and identity in new ways, often focusing on issues of domesticity and sexuality. Though Lynda Benglis’s work is largely sculptural, she is perhaps best known for taking to task the male-centric art world of the 1970s through a series of ads in Artforum magazine satirizing traditional depictions of the female body. Helen Frankenthaler secured her place in the male-dominated color field painting movement through her innovative technique of pouring diluted paint onto unprimed canvas, and played an active role in the print renaissance of the latter half of the 20th century. Mildred Thompson defied the obstacles of being an openly gay, Black female artist and rejected the prevailing narratives of her time to create work that explored meaning through abstract gestures. Howardena Pindell’s work explores social issues such as racism, homelessness, sexism, and xenophobia through her artistic process of deconstruction and reconstruction. Sue Coe puts her political protest into visual form, centralizing themes around the rights of marginalized people and animals.

Through vastly different approaches, the women whose work currently occupies the walls of Brenau’s Sellars Gallery have impacted the trajectory of art history with their unique contributions and compelling visions. While some of the women were reticent to identify as “feminist” artists, their work and their demands to be recognized in a space traditionally reserved for men have sent a message loud and clear: Women belong in the arts, and we’re here to stay.

Allison Lauricella,

Assistant Gallery Director

Virtual Gallery

Click on thumbnail to enlarge image.

- Charmion Von Weigand (American, 1896-1983), “Hieroglyph”, 1958, Gouache on paper, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George E. Seelke, Jr.

- Francine Tint (American, 1943- ), “Long, Long, Long”, c. 1974, Acrylic on canvas, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Marisol (Venezuelan-American; born France, 1930–2016), “Shoe and Hand”, 1964, Lithograph on paper, Gift of Robert and Shirley Bowden

- Hannah Wilke (American, 1940-1993), “Untitled (Puppy)”, 1973, Lithograph on paper, Gift of William Hoken

- Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988), “Untitled”, 1973, Silkscreen on paper, Gift of Margo Leavin

- Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988), “Untitled”, 1973, Silkscreen on paper, Gift of Margo Leavin

- Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988), “Untitled”, 1973, Silkscreen on paper, Gift of Margo Leavin

- Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988), “Untitled”, 1973, Silkscreen on paper, Gift of Margo Leavin

- Ann McCoy (American, 1946- ), “Serpents II”, 1979, Lithograph on paper, Gift of Jimmy and Ellen Isenson

- Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011), “Tout-a-Coup”, 1986, Etching, drypoint, and aquatint on paper, Gift of Jimmy and Ellen Isenson

- Beverly Buchanan (American, 1940-2015), “Happy Shack”, 1986, Lithograph on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Pat Cashin (American, 1931- ), “Untitled”, 1986, Acrylic on canvas, Gift of the artist

- Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011), “Broome Street at Night”, 1987, Etching, drypoint, and aquatint on paper, Gift of Jimmy and Ellen Isenson

- Howardena Pindell (American, 1943- ), “Flight/Fields”, 1988, Etching and aquatint on paper, Gift of Robert and Shirley Bowden

- Mildred Thompson (American, 1936-2003), “Quaver I”, 1989, Lithograph on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Lynda Benglis (American, 1941- ), “Devil’s Home”, 1993, Purified Beeswax, Damar Resin Crystals, Gift of Jimmy and Ellen Isenson

- Kiki Smith (American, 1954- ), “Untitled (Head)”, 1998, Woodcut, collage and hand-coloring on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

- Paula Rego (Portuguese-British, 1935- ), “Mother and Daughter”, 1997, Screenprint on paper, Gift of Drs. John and Patricia Burd

- Kiki Smith (American, 1954- ), “Chickens”, 1998, Etching on paper, Gift of Drs. John and Patricia Burd

- Sue Coe (British-American, 1951- ), “Second Millenium”, 1998, Screenprint on paper, Gift of Drs. John and Patricia Burd

- Elizabeth Blackadder (Scottish, 1931- ), “Still Life with Pagoda”, 1998, Screenprint on paper, Gift of Drs. John and Patricia Burd

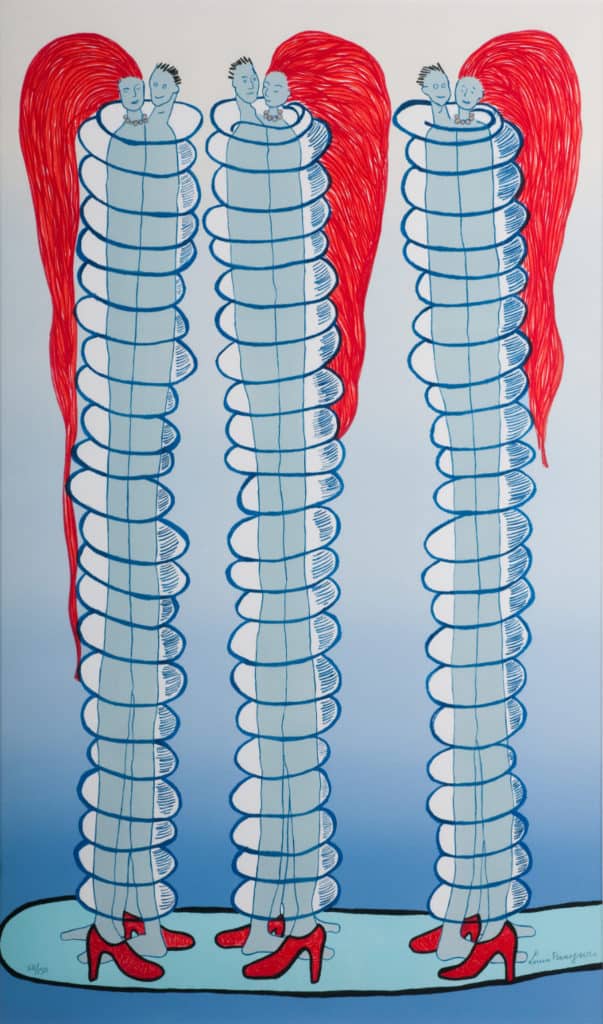

- Louise Bourgeois (French-American,1911-2010), “Couples”, 2001, Lithograph on paper, C.V. Nalley Endowment Purchase

- Margaret Evangeline (American, 1943- ), “Pink Exile”, 2005, Heel Marks and Acrylic on Foil-faced foam, Gift of Hunt Slonem

Charmion Von Wiegand (American, 1896 – 1983)

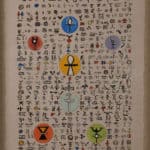

Charmion Von Weigand (American, 1896-1983), “Hieroglyph”, 1958, Gouache on paper, Gift of Mr. and Mrs. George E. Seelke, Jr.

Charmion Von Wiegand was a key player in the mid-19th century art world in America. Her works were influenced by other abstract artists during the time such as Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and Hans Richter. She was also inspired by the writings of Russian occultist and philosopher Madame Helene Blavatsky. Von Wiegand was known as an artist, journalist, art critic and curator, and traveled worldwide in pursuit of her interests.

Hieroglyph was completed when Von Wiegand was branching out from other abstract artists. Like the works of many other abstract artists of the time, Charmion Von Wiegand’s early work typically featured rectilinear shapes with horizontal and vertical lines and primary colors. After the death of fellow abstract painter Piet Mondrian and Von Wiegand’s ever increasing interest in Eastern religion, her works began to feature more curvilinear shapes, downward geometric triangles, and lotus leaves like the ones seen in Hieroglyph.

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011)

Helen Frankenthaler (American, 1928-2011), “Broome Street at Night”, 1987, Etching, drypoint, and aquatint on paper, Gift of Jimmy and Ellen Isenson

This etching, Broome Street at Night, was created by American artist Helen Frankenthaler in 1987. Frankenthaler was a second-generation abstract expressionist and was heavily influenced by the works of Clement Greenberg, Hans Hoffmann and Jackson Pollack. Born in 1928 in Manhattan, New York, Frankenthaler was raised in a progressive Jewish family who encouraged Helen and her sisters to pursue professional careers.

Frankenthaler studied at the Dalton School with Rufino Tamayo, an artist also represented in the Brenau University Permanent Art Collection, and at Bennington College in Vermont with Paul Feeley. Clement Greenberg introduced her to contemporary painting in 1950, and she had her first solo show at New York’s Tibor de Nagy Gallery the following year. Her 1952 painting Mountains and Sea was incredibly influential in the Color Field painting movement. In that work, she pioneered the “stain” technique, in which she poured diluted paint onto unprimed canvas. The resulting color fields looked spontaneous and accidental. Frankenthaler is known as one of the most influential painters of the 20th century.

In addition to painting, Frankenthaler experimented in many other artistic mediums including fiber, ceramics, sculpture and printmaking. In addition to her contributions to the field of painting, she is perhaps best known for her prints. She played a significant role in the “print renaissance” happening in the United States in the second half of the 20th century. This etching with aquatint captures the mood of the iconic New York street at night through the use of color and atmospheric lines.

Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988)

Louise Nevelson (American, 1899-1988), “Untitled”, 1973, Silkscreen on paper, Gift of Margo Leavin

Louise Nevelson is known as one of the most important figures in 20th-century American sculpture. Born in present-day Ukraine, Nevelson emigrated to the United States with her family in the early 20th century and was attending classes at the Art Students League of New York by 1930. In 1935, Louise Nevelson taught mural painting through the Works Progress Administration (WPA) at the Madison Square Boys and Girls Club in Brooklyn. She was employed by the WPA easel painting and sculpture divisions from 1935 until 1939 – an opportunity for women artists to contribute to post-war recovery in a meaningful way at a time when gender stereotypes often prevented the celebration of women’s art.

Louise Nevelson is most well known for the monumental, wooden sculptures she devoted her late career to. These pieces often appeared puzzle-like and were painted in monochromatic black or white palettes. However, a significant moment in her career came through the practice of printmaking at a six-week artist fellowship at Tamarind Lithography Workshop in Los Angeles during the early 1960s. Nevelson was offered the fellowship at a time where her funds were depleted, she lacked inspiration, and she was making her way as a women artist on the heels of a divorce from her wealthy husband. Nevelson became the most productive artist to complete the fellowship to that point, and made exceptionally creative works with interesting textile effects via lithography stone and unconventional printing materials. This period of productivity reinvigorated Nevelson, who returned to her home in New York and solidified her commercial and critical success.

The four untitled silkscreen prints from 1973 on display represent this post-fellowship Nevelson, inspired and determined. These pieces reflect the sculptural work that Nevelson grew to be known for – the dark, subtle tones and monolithic shapes are reminiscent of the wooden sculptures she created. Nevelson was a key figure in the feminist art movement, as she examined the idea of what constituted “women’s art” by creating her “dark, monumental, and totem-like artworks which were culturally seen as masculine”. Nevelson chose to reject the idea that “masculine-feminine” labels were reflected in art – rather, art reflected the individual. Nevelson herself embraced and claimed a uniquely feminine persona through large scarves, dramatic dresses, overly large false eyelashes, and a sexually liberated lifestyle.

When Nevelson had her first solo exhibition in the United States in 1941, one review read: “We learned the artist is a woman, in time to check our enthusiasm. Had it been otherwise, we might have hailed these sculptural expressions as by surely a great figure among moderns”. Much later in Nevelson’s career, when she had solidified her place as one of those great moderns, she was asked about the sexism faced throughout her career. She responded: “I am a women’s liberation.”

“Louise Nevelson”. Artists. The Art Story. 2020. Retrieved September, 2020.

Beverly Buchanan (American, 1940-2015)

Beverly Buchanan (American, 1940-2015), “Happy Shack”, 1986, Lithograph on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

Beverly Buchanan was a southern woman to her core: vibrant and welcoming. She was born in Orangeburg, South Carolina, but left the South for a time to pursue a degree in health education in the 1960s. She took a course at the Art Students’ League in 1971 and this started her down a new path. She befriended artists Norman Lewis and Romare Bearden and began to tell her stories with visual art. Using her childhood as a source, Buchanan began to bring to life the stories, people and architecture of the Rural Southern landscape. These varied viewpoints are united in a series of works based around the indigenous Southern Architecture known as the “shotgun shack.” These little houses vary in color, media, and scale. By the 1980’s Buchanan was back in the south and living in the greater Atlanta area as a successful working artist when Wayne Kline, leader of the Atlanta-based Rolling Stone Printing Press, approached her – but she was hesitant to collaborate. In an interview with Catherine Fox from The Atlanta Journal/The Atlanta Constitution in 1987, Buchanan tells the story about her experience with Rolling Stone Press:

“Wayne started talking about making a print about a year ago, but I wasn’t interested,” she recalls. “I had studied with Norman Lewis and Romare Bearden, and they were so against prints. Wayne really had to convince me. I thought I’d lose control of my work, that someone else would be in charge. I was intimidated by the stone.” The experience, however, “was wonderful,” she says. “I always felt in control, and Wayne was there when I needed him… First, I did a trial print to get the feel of what it’s like to draw on the stone and see what it looked like printed. It’s different than drawing or painting…” Working with color was different, too, because in printmaking each color is printed separately. “It’s like seeing things in a puzzle and imagining it together,” she says. “After the trial print, I got excited. Then, I got obsessed. Now I want to do another one.”

Happy Shack was the result of this collaboration.

Howardena Pindell (American, 1943- )

Howardena Pindell (American, 1943- ), “Flight/Fields”, 1988, Etching and aquatint on paper, Gift of Robert and Shirley Bowden

Howardena Pindell is an American mixed media artist and painter. Pindell was trained as a painter at Boston University and Yale University, and is known for exploring process through her artmaking – utilizing unique textures, colors, and compositional structures across her media. Much of Pindell’s work is political, addressing issues of racism, feminism, slavery, and exploitation.

Howardena Pindell co-founded the first artist-directed gallery for women artists in the United States in 1972 – the A.I.R. Gallery – asserting her place in art history as an African-American woman. The A.I.R. Gallery allowed women artists to curate their own exhibitions and take risks that traditional galleries were not willing to allow. Along with her work for A.I.R, Pindell spent 12 years of her career working in various capacities for the Museum of Modern Art. These unique influences converged to inform Pindell’s work in the late 1970s and 1980s, as she was exposed to a number of exhibitions while at A.I.R. and MOMA that inspired her process. One exhibition that Pindell cites resonating with strongly was the MOMA’s collection of Akan batakari tunics in an exhibit called African Textiles and Decorative Arts. These influences led Pindell to the process she is most well-known for – one in which she deconstructs and reconstructs her paintings by cutting the canvases and sewing them back together. This can be seen as a reference to the African textiles that so heavily influenced her, as well as her interest in a labor- and process-oriented approach to her work.

The work on display, Flight/Fields, is representative of a multi-year printmaking collaboration with Judith Solodkin of Solo Impressions, Inc. Master Printer Solodkin completed a print portfolio of A.I.R. artists in the early 1970s, and this was the first time that Pindell had worked with a Master Printer. Solo Impressions printed many of Pindell’s works thereafter. Flight/Fields has the appearance of de- and re-construction prominent in much of Pindell’s painted works. The print’s subject was depicted by Pindell many times – the grid between farm pastures as she flew over them during travels. Pindell dislikes flying, but has conquered that fear throughout her years of travel – much as she has conquered over the critics of her increasingly political later works. “There was a nostalgia for my non-issue related work of the 1970s”, she says. But her dedication to combating racism and discrimination through her art, travel, writings, and lectures gives her the strength to fly in the face of misguided nostalgia.

Mildred Thompson (American, 1936-2003)

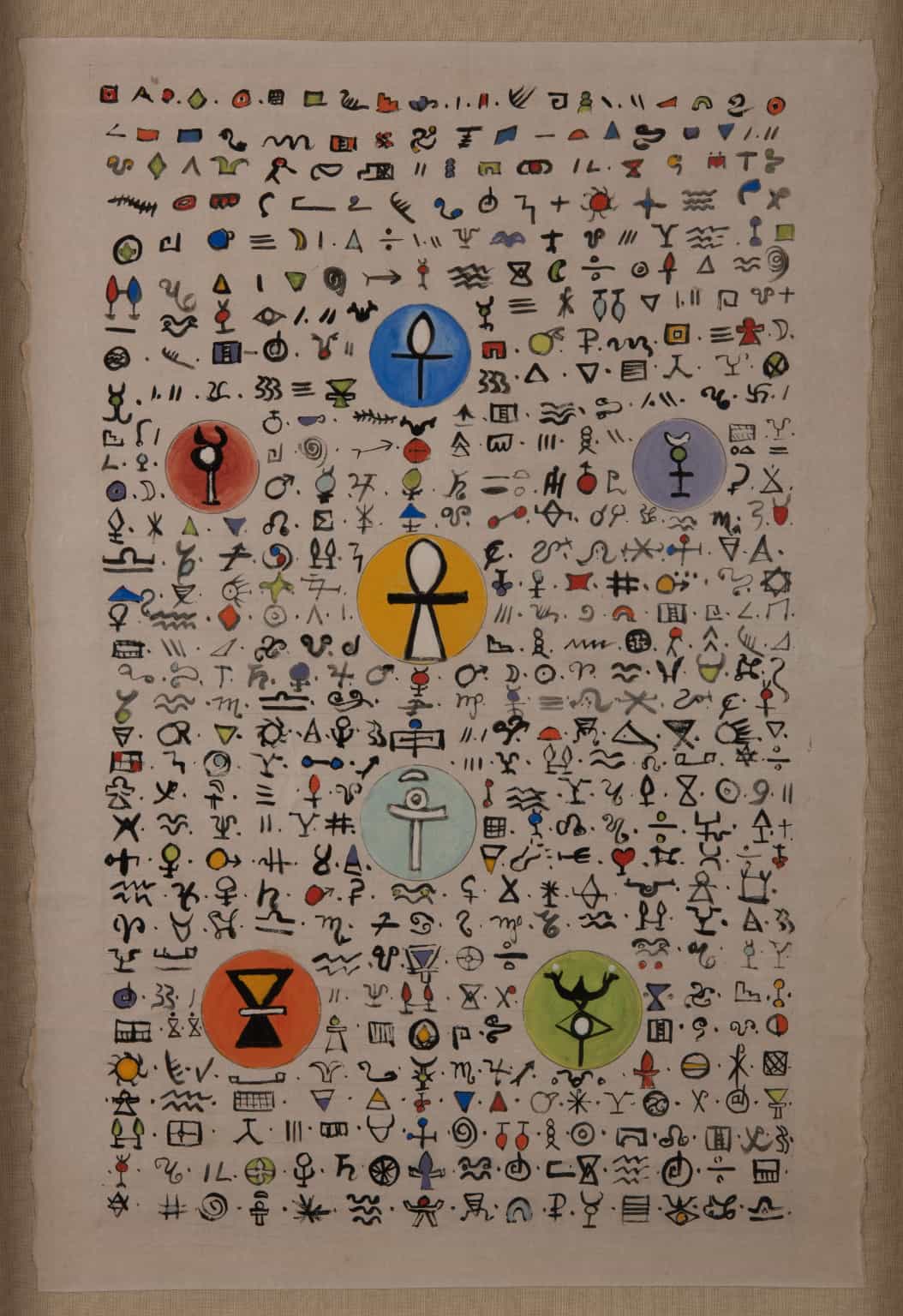

Mildred Thompson (American, 1936-2003), “Quaver I”, 1989, Lithograph on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

“My work in the visual arts is, and always has been, a continuous search for understanding. It is an expression of purpose and reflects a personal interpretation of the universe. Each new creation presents a visual manifestation of the sum total of this lifelong investigation and serves as a reaffirmation of my commitment to the arts. This exploration has led me through the various techniques of painting, drawing, sculpture, printmaking and photography.”

-Mildred Thompson

Mildred Thompson is an American artist who explored various genres of artmaking throughout her career spanning over four decades. Thompson was born in Jacksonville, Florida, in 1936. She began her formal training in art in 1956 at Howard University in Washington, D.C., where she studied under James A. Porter. After receiving her BFA at Howard, she went on to study at the Brooklyn Museum Art School in New York. Feeling ready for a change, Thompson moved to Germany to study at the Art Academy of Hamburg. This was a period of tremendous growth for her as an artist. At the academy, she was introduced to various printmaking techniques including lithography and etching, which would become an integral part of her artistic practice.

When Thompson returned to the United States in 1961, she faced much discrimination as a Black female artist. In Germany, she had found acceptance and felt free to create, but she encountered a different atmosphere in her home country. After struggling to find venues to show her work and gallery representation in the states, she returned to Germany where she was able to exhibit and sell her work. After 10 years in Germany, she returned to the United States in 1975 and found the social climate much improved. In 1986, after participating in artist residencies in Florida and Washington, she settled in Atlanta, Georgia, where she would spend the remainder of her life. During her years in Atlanta, Thompson taught at Agnes Scott College, Morehouse College, Spelman College and the Atlanta College of Art, and served as the associate editor of Art Papers.

Though Thompson began her career as a figurative painter, her work shifted to pure abstraction in the early 1970s. Unlike many of her contemporaries, Thompson shied away from addressing gender and race in her work in favor of exploring abstract theories and the mysteries of the universe. Quaver I, like much of her work, displays a predilection for mark-making. The lines almost dance as they interact with each other, creating a sense of movement. Thompson sought to give imagery to things that cannot be seen by the human eye, such as sound, time and space. Her works are imbued with a sense of chaos and mystery, paralleling the abstract concepts from which she drew inspiration.

Kiki Smith (American, 1954-)

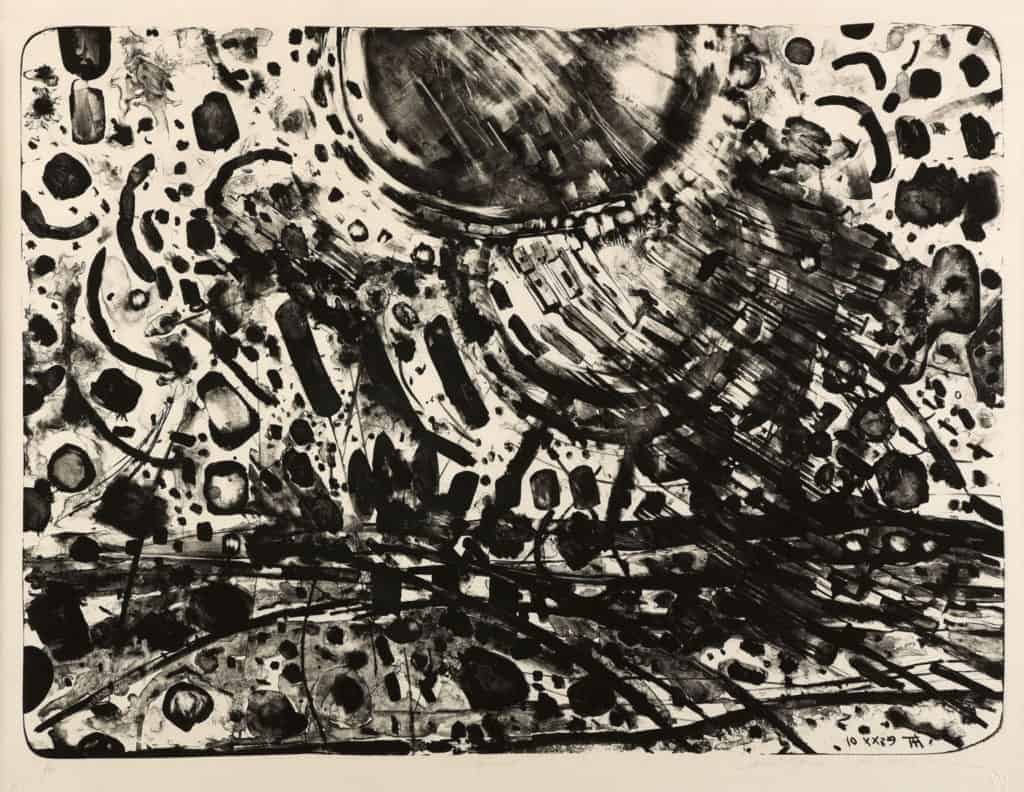

Kiki Smith (American, 1954- ), “Untitled (Head)”, 1998, Woodcut, collage and hand-coloring on paper, Brenau Art Endowment Purchase

Kiki Smith was born in West Germany in 1954, but moved to the United States with her family as an infant. Smith has worked in a variety of media, including sculpture, printmaking, film, and textile. She is consistent with her themes, however – birth and regeneration, sex, and the human condition. Smith’s early upbringing in the Catholic Church and her interest in the human body has shaped much of her work. There were several traumatic events in Smith’s life – including the death of her father in 1980 and the loss of her sister to AIDS in 1988 – that led Smith to truly explore mortality and the limits of the human body. She did not shy away from subjects that were considered taboo – such as bodily fluids and functions.

In the 1980s, spurred on by the deaths in her family and general state of the world, Smith embarked on an exploration of printmaking processes. She worked with a New York City artists’ group called Colab to create a number of posters containing political statements. By 1989, Smith’s work had been featured in the Brooklyn Print Biennial, where it was seen by Bill Goldston – the director of New York print studio ULAE. Goldston was impressed by Smith’s work and invited her to print at his studio, and since then Smith has made 40 editions with ULAE working in a variety of print processes.

Untitled (Head) is an example of Smith’s work with ULAE (the ULAE stamp can be seen in the bottom left corner). The piece was created in 1995 as a limited edition of 47 to support the New York Foundation for Contemporary Art’s (FCA) artist granting program. The print was available exclusively from FCA and was purchased through the Brenau University Art Endowment.

Kiki Smith came of age as an artist in the late 1970s, when the second wave of Feminism was coming to an end and artists were seeking to explore women’s place in the world socially, culturally, and politically. Smith’s unabashed attention to the human condition and her determination to call attention to the body – the strong and beautiful parts as well as the hidden and confusing parts – have positioned her as an important figure in 20th and 21st art history. Smith has said, “I always think the whole history of the world is in your body”, and that is what she represents through her work.

Sue Coe (British-American, 1951- )

Sue Coe (British-American, 1951- ), “Second Millenium”, 1998, Screenprint on paper, Gift of Drs. John and Patricia Burd

Sue Coe is an English artist working primarily in printmaking, drawing, and illustration. Coe began doing work for newspapers at the age of sixteen, and since then her life has been dedicated to editorial art and narrative. Her work is highly political and often serves as an intentionally uncomfortable commentary on issues such animal rights, the rights of marginalized people, and capitalism. Her work has been exhibited and collected internationally, and her illustrations are often published in magazines, newspapers, and books.

Sue Coe grew up in Straffordshire, England behind a hog farm and slaughterhouse, which caused her to develop a strong passion for fighting against animal cruelty. She recalls being continuously exposed to the animals’ screams and the strong stench coming from the slaughterhouse. Coe translates these memories and traumatic experiences into visual form for works such as Second Millenium. The viewer is assaulted by a nonsensical scene full of gore – a large meat grinder springs from a severed human foot serving as the focal point, while the surrounding environs include a host of dead and dying animals, human and animal carcasses, and man-made creations delivering various animals to their deaths. The complexities of the piece are reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch’s (1450-1516) Garden of Earthly Delights– a dramatic, fantastical, and grotesque view on the religious transitionary narrative of Eden to the Last Judgment. In both the historical Netherlandish painting and the modern Sue Coe print, there is no emphasis on realistic perspective or a sense of space. Figures are overlapped, the sense of scale is exaggerated, and the color palette is unnerving at best. These artistic choices intentionally create a chaotic, disturbing, and thought-provoking atmosphere for viewers in both cases.

Sue Coe has dedicated her life and her art to fighting for the rights of the marginalized, and does not shy away from making her viewers uncomfortable. Second Millennium is an example of Coe’s desire to represent those victims, human or animal, oppressed by things beyond their control. Her works are often auctioned off at fundraisers for progressive causes. When it comes to feminism, Sue Coe has expressed her criticism of the movement as being controlled by America’s dominant classes. And when asked, “How does it feel to be a woman artist”, Sue Coe is known to respond: “I mean, how does it feel to not be?”

Louise Bourgeois (French-American, 1911-2010)

Louise Bourgeois (French-American,1911-2010), “Couples”, 2001, Lithograph on paper, C.V. Nalley Endowment Purchase

Louise Bourgeois was prolific in a variety of media throughout her career, working in large-scale sculpture, installation, painting, and printmaking. Her work defied categorization, drawing comparison to Abstract Expressionism, Feminist Art, and Surrealism at any given time. Bourgeois’ work was tied across media and years by her recurrent themes of sexuality and the body, the family and domesticity, death and the unconscious. Childhood trauma and hidden emotion related to her father’s infidelity inform much of Bourgeois’ work, which tends to emphasize the woman’s role as mother and challenges patriarchal dominance. Because she was not tethered to any particular art historical movement, Louise Bourgeois was known as a pioneering artistic voice across genres.

While Bourgeois might be best known for her large scale sculptures, she was an active printmaker at varying times during her career – first in the 1930s and 40s when she arrived in New York, and then again in the 1980s. In those earlier years, Bourgeois worked on a small press in her home and then transitioned to the well-known print shop Atelier 17. Bourgeois shifted her attention to sculpture after her initial period of printmaking productivity – but in her seventies she set up her old home press and began printing again. Over the course of her life, and bolstered by those two periods of great productivity, Bourgeois created over 1,500 printed compositions.

The included print Couples comes from the later period of productivity, when Bourgeois was 90 years old. Upon first glance, the piece may appear to present the image of three loving couples wrapped up together. Questioning the piece’s content and motivation, however, leads to the question – what is binding the couples together, and did they choose it? This piece is referential to a performance piece Bourgeois created earlier in her career, called She Lost It. Bourgeois created a banner with the following story written on it:

A man and a woman lived together. On one evening he did not come back from work, and she waited. She kept on waiting and she grew littler and littler. Later, a neighbor stopped by out of friendship and there he found her, in the armchair, the size of a pea.

The insidious result of the narrative references the insecurities and anger Bourgeois felt after witnessing her father’s affairs as a child. For the original performance, on December 5, 1992, this banner was used as a centerpoint. The banner began wrapped around a single actor, and as it was unfurled for the audience to read it slowly began wrapping up others until eventually it wrapped around a couple, as shown in the lithograph. The original actor held a pea in his hand – referencing the abandoned woman.

The spirals wrapping the three sets of people in Couples have a discomforting effect – overall, the spiral in Bourgeois’ work represents “the fear of losing control” and the experience of “giving up control; of trust, positive energy, of life itself.” Bourgeois questions whether we can control the chaos, and whether we want to.

” Louise Bourgeois: The Spiral”. Exhibitions. Louise Bourgeois: The Spiral. 2020. Retrieved September, 2020.